Fr Dick O’Riordan: A Township Missionary Looks Back

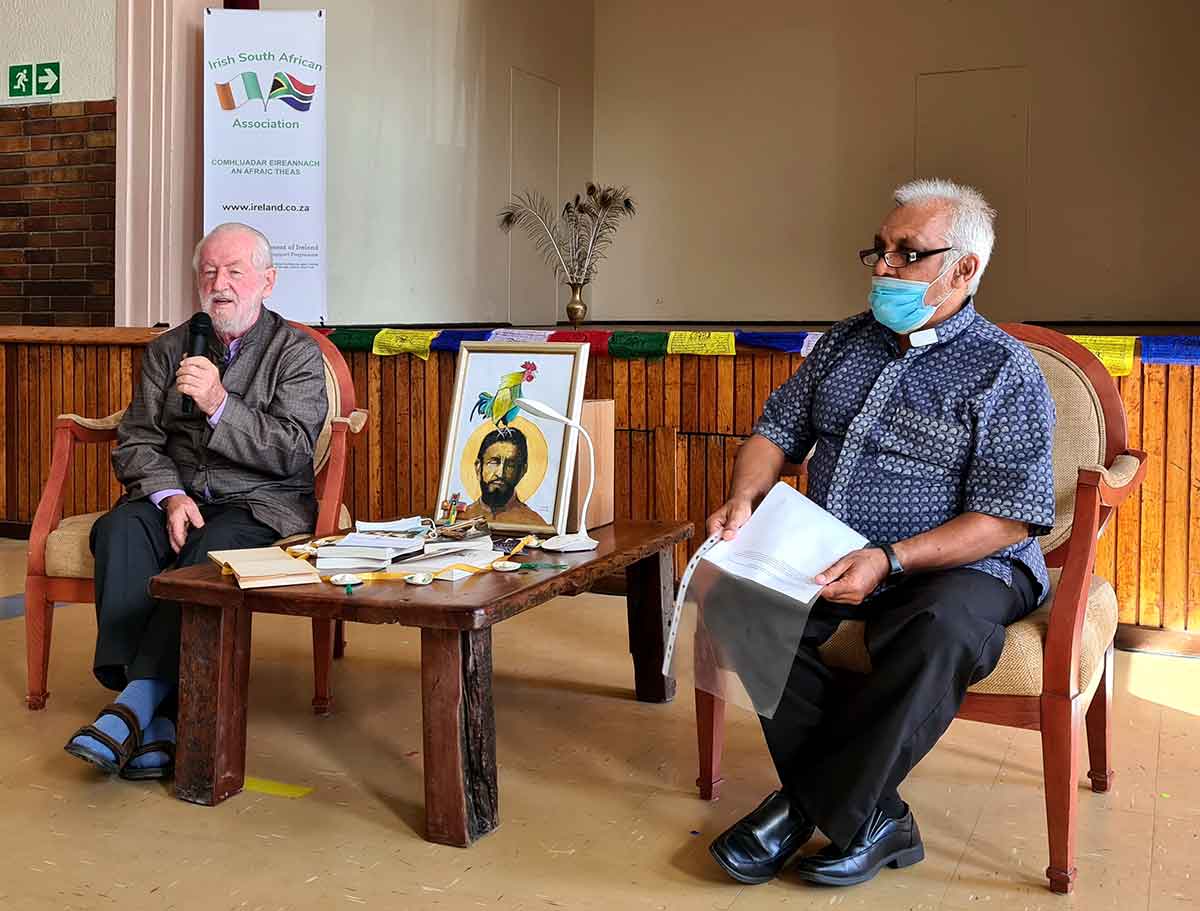

Fr Dick O’Riordan (left) speaks at the launch of his memoirs at St Mary of the Angels church in Athlone, Cape Town, as Fr Peter-John Pearson listens.

Fr Dick O’Riordan, an Irish missionary, has written his memoirs of ministry in South Africa, and his run-ins with the apartheid regime. He spoke to Mike Pothier.

Cape Town priest Fr Dick O’Riordan recently published his memoirs, entitled Roots in Exile: Fifty years as an Irish priest in Africa. The book has been hailed by the BBC’s international correspondent Fergal Keane as “an account of a life well lived in which choices were made with courage and principle”.

Born in rural County Cork in Ireland on June 2, 1944, Fr O’Riordan was ordained in 1967 for the archdiocese of Cape Town. In 1971 he was appointed parish priest of St Gabriel’s parish in Gugulethu but was expelled by the apartheid regime in 1978. Two years later he returned, to the “independent” homeland of Transkei. In 1986 he was detained by the Transkei government for a month, and then expelled again. After working among exiles in Zimbabwe, Fr O’Riordan returned to South Africa in 1992, serving in the Cape Town parishes of Khayelitsha and Koelenhof until his retirement from parish ministry in 2015.

Mike Pothier: You write movingly about the Irish diaspora and the feelings associated with leaving family and country for a life thousands of kilometres away. Why did you decide to become a missionary priest, instead of serving in Ireland?

Fr O’Riordan: For me, as for many others before me, there was no debate about it. The Irish Capuchins, the Kiltegans, and the Columban priests working in Peru, El Salvador, Zambia, South Africa, Japan and South Korea visited our primary schools regularly. They left us their magazines and I can still see the picture of a priest paddling his dugout canoe in the Philippines. I wanted to be there, though I ended up in Africa, of course.

Also, one of my uncles and some of my cousins and neighbours became Sisters, Brothers and priests, many of them in faraway places, so it was a natural choice for me.

And when you settled into your first posting as a parish priest, in Gugulethu, you found a number of similarities with the life you’d left behind in Ireland.

Yes, many of my parishioners had grown up on the land, as I did, and they loved community activities, which often reminded me of the harvest days in Ireland. At the Easter weekend they invited neighbouring communities, who came with their sheep and blankets for the all-night Passover Vigil. There was also a similar sense of warmth and hospitality — the people of Gugulethu welcomed me as one of their own.

Cardinal Owen McCann, a towering figure in the South African Church, was your bishop for the first couple of decades of your priesthood. From the way you write about him, one senses that although he sometimes left you frustrated, there was also a real warmth and affection in the relationship?

Cardinal McCann is quoted as having said: “I like being a cardinal.” He seemed very conscious of his status as a Prince of the Church, and he sometimes seemed to struggle in his calling as shepherd to the flock. As a white South African, he had had very little contact or interaction with black people on an equal basis. But some visits to smashed-up shacks in Matroosfontein and to mourning families in Gugulethu, whose loved ones had been shot dead by the riot police, opened his eyes to the realities in his own country.

Later, in a packed courtroom, at one of my court cases, he sat on the floor at the back, supporting me, and I grew to admire his openness and solidarity during our conflicts with the evil apartheid laws. It made me reflect that bishops are not made, they become.

Although most of us did not see him as an emotional person, or given to intimate personal sayings, he once called me “a young chicken, but a good chicken”, which I took as a compliment.

Exile is another central theme in the book. In 1978 you were deported from South Africa and in 1986 you were also deported from the Transkei. You write that “the bottom fell out of my life”. These were some of the darkest days of apartheid. When you left these shores, were you confident that you would come back someday and resume your ministry?

As I passed by Gugulethu on the day I left Cape Town in February 1978, I cried out: “I will never see you again.” It felt like I had been torn out of the nurturing womb of Africa. I cried all the way to Port Elizabeth [now Gqeberha], as I went to visit some of my fellow Irish priests there, my homeboys. One of them, Mgr Brendan Deenihan, like a brother, drove me to Lesotho, where we received wonderful hospitality from Archbishop Alfonso Morapeli of Maseru.

I later worked in Transkei from 1980, but in 1986 I was forced to leave there because I was highlighting the horrific killings of Matthew Goniwe and the Craddock Four by the security police.

At that time, some of the cornerstones of apartheid — like the stealing of land, racially segregated residential areas, pass laws, and others — were on the surface working perfectly. With the brutality and the military might of the regime, I left with a heavy heart, resigned to my “phuma phela” — out forever. I was aware of the underground resistance, but I feared it would take too long. So, although I never lost hope of coming back, I can’t say I was confident about it at the time.

You say that the people you served taught you how to be a priest. At a practical level, what lessons did you learn from them?

The first lesson I learnt was to take off my watch! In Africa, time is for people; and the people showed me that priesthood, like time, is also for people.

And then I was so moved at how, despite being treated as less than human by the evil system of apartheid, people kept their dignity — I will never know how they managed it. Amidst all the daily insults and humiliations, the people continued to practise their culture and their customs, and they lived out their strong faith. Everyone was welcome, even me. They helped each other to carry their cross — which is how I came to understand Ubuntu.

I also learnt that I was not there “to bring God” to the people. Many of them had names with deeply religious meanings, like Nkosinathi (the Lord is with us), Khotso (Peace), Zamankosi (Try the Lord), Themba (Hope). Some priests would not accept these supposedly “pagan” names at baptism. They told the people to find “Christian” names — like mine, Richard, which means “iron rule”! As other missionaries have said, “When I arrived, I found that God was there already.”

Roots in Exile: Fifty years as an Irish priest in Africa is available from the Catholic Bookshop, Cape Town, at R250. Ordered online at www.catholicbookshop.co.za or e-mail or call 021 465-5904.

- Furgione Graduates Rome Film School with Honours - March 3, 2026

- Mass Readings: 8 March – 15 March, 2026 - March 3, 2026

- Pope Leo: Jesus is Living Wisdom - March 2, 2026