Breaking the alliance of abuse in Church

The Catholic Church is now looking to recover from the sex abuse scandal. COLLEEN CONSTABLE looks at why things went wrong, and how children can be kept safe in the Church.

Scripture teaches us to �…hate what is evil and hold on to what is good….Do not be conquered by evil but conquer evil with good� (Romans 12:9, 21).

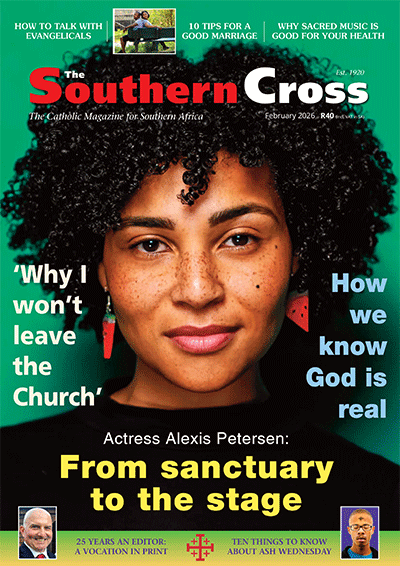

I am a cradle Catholic who has no intention of leaving the Church, irrespective of the clergy sexual abuse scandal. I love the Church: it is where I discovered Christ and follow him. I am part of the one billion Catholics worldwide who are hurting, ashamed, deeply disappointed, yet glad that secrets are revealed and immoral conduct exposed.

Jesus taught us: �Nothing is concealed that will not be revealed, nor secret that will not be known� (Mt 10:26). I support criminal prosecutions of clergy for sexual abuse of minors and that such clergy be defrocked. And I have confidence in Pope Benedict�s commitment to eradicate clergy sexual abuse.

Pope Benedict during last month�s visit to Malta promised abuse survivors that perpetrator clergy will be held accountable for the sexual abuse allegations, which date back between 1980 and 1990.

A theory of gender-based violence is also transpiring: pornography and perversity. An online report from The Economist suggested that in Brazil three clerics have been suspended for their alleged involvement in making a sex video involving youth.

The Church is faced with the manifestation of a societal problem visible within the ranks of the clergy: gender-based violence in the form of statutory rape and sexual exploitation of minors, manifested through paedophilia (the sexual preference of adults for prepubescent children), ephebophilia (the sexual preference of adults for mid-late adolescents, especially boys) and hebephilia (the sexual preference of adults for boys and girls reaching puberty).

A proper study to determine the actual causes and motivations of clergy sexual abuse and the perceived tendency towards boy children, placing them at a higher risk than girls, would assist to prevent future abuse and exploitation of children. And it will answer the empirical question of whether the unavailability of an adult partner is contributing to exploitative behaviour by some clergy, an assumption that many choose to make carelessly rather than scientifically.

The 2006 Report of the Independent Expert For the United Nations study on violence against children indicates that adults in trust positions such as teachers, police, clergy, parents or relatives, employers and sport coaches form the perpetrator profile of violence against children. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that during 2002 between 150 million girls and 73 million boys under 18 years experienced forced sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual violence worldwide.

The powerful Southern Cross editorial �The boil must be lanced� (April 7-13) provides an objective perspective and gives hope for the future. Archbishop Buti Tlhagale�s Chrism Mass homily this year was direct about clergy sexual abuse: he eliminated denial and defensiveness. He referred to abusers as �wolves wearing sheep�s skin�, and acknowledged that �because of the scandal the authoritive voice of the Church has been weakened� and �trust has been compromised�.

The voice of the archbishop represents the feeling of the faithful; he said what they wanted to say, but may not, to avoid being frowned upon or be marginalised. He understands the concern about the integrity of the priesthood: the faithful seek a holy priesthood. Archbishop Tlhagale understands that the pressure on the Church to ensure and prioritise the safety of minors is mounting from all sectors.

Clergy who commit sexual abuse against minors had their sexual disorders before they entered the priesthood. They may have acted upon their disorders and sexual preferences and escaped the scrutiny of the community as sexual crimes are consider to be the most under reported crime worldwide. And others may have been known, yet chose to remain silent.

Ordination of such candidates into a holy priesthood was the outcome of a distorted recruitment and discernment process relying mostly on spiritual compatibility.

It created a dangerous combination of clergy: of a group who truly seeks and upholds the integrity of a holy priesthood; and a tiny group of potential abusers. It becomes an environment that creates the breeding place for exploitation of children, sexual coercion and �male�male alliances�.

Abusive priests are not alone: some bishops are alleged to have protected abusive clergy through secrecy and transfers, actions that encouraged a male-male alliance or coalition and a subculture of hypocrisy, protection and support for predators.

A subculture that tolerated sexual exploitation of minors by clergy was born: perpetrators knew they held the power. A brother-priest would not turn against another brother-priest: a son-priest would not testify or cooperate to facilitate accountability of another son-priest, even if the most innocent and most vulnerable of our society were harmed.

Cardinal Dario Castrillon Hoyos, then prefect of the Congregation of Clergy, in a 2001 letter congratulated Bishop Pierre Pican of Bayeux-Lisieux for not reporting a priest to the police for alleged sexual abuse of minors, as French law demands. (Bishop Pican received a three-month suspended sentence; the accused priest was sentenced to 18 years in prison.)

It is this subculture of secrecy and falsehood intended to conceal and compromise the truth, the impunity and exploitation that must now be changed into a culture that truly upholds the teachings of Christ and integrates principles of good governance and ethical leadership.

All this happened right under the noses of the faithful: there may have been whisperings about habits and doings of clergy, suspicion that something is wrong � and a fear to act. That fear was caused by a system that although propagating transformation in terms of real participation of the faithful in issues affecting the Church, still has the capacity to silence active voices.

As the faithful we may have not been vigilant enough: we trusted too much in the good will of the clergy, forgetting that even among them evil may at times persist. The faithful must now become active partners in the prevention of sexual abuse of children.

Ethical leadership will be crucial to change that subculture and establish a culture that protects children, upholds the integrity of the priesthood, and ensures good governance and sustainable management of all future sexual abuse complaints against clergy. The complexity of the legal system will only increase the accountability of the Church as survivors may continue to rely on the Church to take appropriate action against perpetrators, although they have a huge distrust towards the Church�s internal investigation process and mechanisms.

The reporting of complaints to authorities and credible investigations for internal purposes is crucial, and so is the willingness of priests to testify against other priests as and when required to do so.

The current investigative process is widely questioned by complainants. This may decrease the legitimacy of the protocol committees. When complainants doubt the integrity of the investigation, irrespective of the profile and expertise of the group, it is a vote of no confidence in the response of the Church.

The important aspect is to re-establish the trust relationship with complainants, and that can only be done by providing credible and transparent investigations. Should the chairperson of the professional conduct committee be a member of the clergy (who could also be at risk of being investigated at some point)?

To avoid repetition of past mistakes, the process needs to progress into long-term prevention and detection mode. It is now a period of risk-control, compliance and problem-solving: a process where every diocese should accept the reality that allegations of sexual abuse of minors may emerge anytime.

A comprehensive prevention strategy integrating a problem-solving approach at diocesan level is necessary. It should prioritise the survivor and ensure compliance where there is substance to complaints through dealing with the alleged perpetrator in a preventative and accountable manner.

It must acknowledge that there are further parties to the situation: the family of the survivor, the family of the perpetrator, the faithful of the parish and diocese and also the broader society. It indicates the need to have a constructive partnership with them to provide required support to affected persons, restore the trust that has been broken, and facilitate a process of rebuilding a hurting family and parish, diocese and community.

The prevention strategy should also address partnerships with other stakeholders, such as Childline, to establish cooperative relationships; a diocesan advocacy campaign to empower parish councils and parishioners on the prevention of sexual abuse of minors by clergy; a programme for clergy to create awareness on prevention of sexual abuse of minors, theories of gender-based violence, leadership and how to cooperate with criminal justice processes to strengthen victim support and increase offender accountability; a programme for the youth to ensure their participation in how to sustain their safety and prevent violence against minors, and an awareness campaign encouraging minors to report any physical or sexual abuse by clergy. All this makes prevention of child sexual abuse not a reactive exercise when a complaint has been lodged, but a 365-day pro-active approach.

The deadly silence that exists at parish level whilst this crisis has made headlines should be replaced with an openness and willingness to engage the local ordinary on how to support him in this challenging task. It is about the children of the nation and the future of the Church, which lies in the youth of today.

I thank all those priests who go about their daily life without compromising the integrity of the priesthood and the Church and without endangering the lives of children.

Although they now endure scrutiny because of the destructive behaviour of �brother-priests� they also hold the trump card: to testify against a �brother-priest� when children have been violated and the integrity of the priesthood compromised.

Colleen Constable is an independent consultant based in the Western Cape. Her interests includes leadership, policy, management and spirituality.

- When was Jesus born? An investigation - December 13, 2022

- Bishop: Nigeria worse off now - June 22, 2022

- St Mary of the Angels Parish puts Laudato Si’ into Action - June 17, 2022