St George ‘the Dragon-Slayer’ was a Real Person

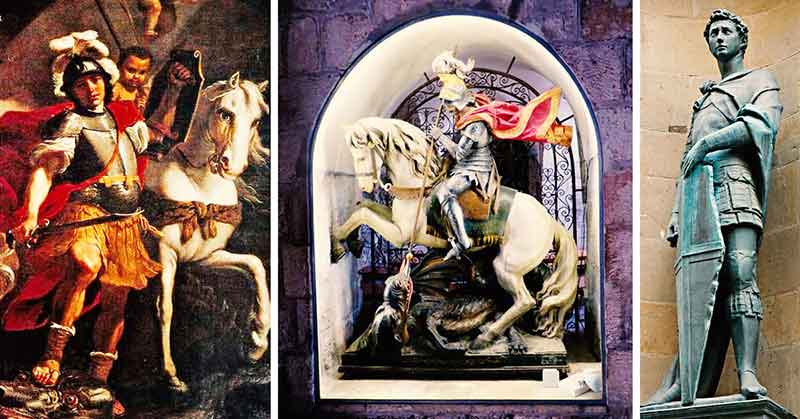

(Left) St George puts his foot on the vanquished dragon, in a painting by Mattia Preti (1613–99) in St George’s cathedral, Malta. (centre) St George slays the dragon, represented at St Catherine’s church in Bethlehem, Palestine. (Photo: Günther Simmermacher). (right) St George, in a bronze copy of a marble statue by Donatello (1386–1466).

St George slayed no dragons, but he certainly was a real person who was martyred 1700 years ago. Günther Simmermacher looks St George’s life.

St George at a Glance

Born: 3rd century in Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey)

Died: April 23, late 3rd/early 4th century

Canonised: 496 AD

Feast: April 23

Attributes: Soldier with lance, often depicted slaying a dragon

Patronages: Soldiers, scouts, farmers and field workers, shepherds, equestrians, skin disease sufferers, lepers, syphilitic people, England, Ethiopia, Georgia, Palestine (unofficial)

The legend of St George and the dragon may tempt us to dismiss this martyr of the early Church as a character of legend who never existed. To be sure, the slaying of the dragon is a legend (or metaphor) that had its roots in the 11th century — but St George most certainly did exist, and his cult is one of our faith’s oldest.

Though England has claimed St George as its own — the English flag bears the St George’s cross — the man was from modern-day Turkey and died a martyr’s death in Palestine, probably in the late 3rd century or shortly after. Other than a few ancillary facts, this is all we know for certain. But ancient writings, going back to the 5th century, fill in the basic story of St George.

According to these writings, George was born of a Greek father and Palestinian mother, named as Gerontius and Ploychronia, in Cappadocia, in modern-day Turkey. Both parents were Christians. Eventually George followed in his father’s footsteps to become a Roman soldier.

George’s legends

There are three main streams of tradition on the life of St George: Latin, Greek and Muslim (he is venerated in Islam as well). We will consider the two Christian traditions, which go back to at least the 5th century, and probably to the 4th century, when the Palestinian historian Eusebius noted the popular veneration of St George.

In the Greek version, Gerontius was martyred for his faith when George was 14, whereafter mother and son moved to her old home in Palestine. After his mother’s death, George joined the army.

From here on it gets a bit murky. The earliest extant version of the hagiography says George was persecuted and martyred by one Dadianus, whom history doesn’t record at all. So later texts changed the persecutor’s name to Emperor Diocletian, who indeed was a brutal persecutor of Christians (and other non-pagans) in 303 AD, especially within the military. All texts agree that George met his end by decapitation on April 23, but nobody knows in which year.

Legend has it that the execution was witnessed by Alexandra of Rome — who, according to tradition, was the wife of either Diocletian or the prefect Dacian — prompting her conversion to Christianity and subsequent martyrdom. After the execution, George’s body was taken to Diospolis in Palestine (later Lydda, now Lod in modern-day Israel) for burial. There the local Christians venerated him as a martyr, and his tomb is still there.

Who killed George?

The Latin version, which was recorded no later than the 6th century, agrees with the Greek narrative up to the martyrdom. Here the persecutor is Dacian, called the “Emperor of the Persians”. There was no such emperor, and the prefect Dacian was persecuting Christians in modern-day Spain, far from where George was martyred. Later versions of the Latin legend supposed that Dacian might have been a Roman judge serving under Diocletian or maybe Emperor Decius (249-51). Or might St George have met his end in the region of Dacia, which included Romania and was a Roman province until 271 or 275 AD?

George’s death, according to the Latin legend, was preceded by 20 tortures over seven years, and these inspired 40900 pagans who witnessed these to convert to Christianity, including Alexandra of Rome. And when George finally died, legend claims, the ghastly persecutor Dacian was carried away in a whirlwind, never to be seen again.

Whatever the facts of his death, the cult of St George spread quickly. One of the first churches in the Holy Land, built in the first half of the 3rd century at Lydda and financed by Emperor Constantine, was almost certainly dedicated to St George. And in 494, Pope Gelasius I, acknowledging gaps in the hagiography of St George, hailed him as one of the saints “whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose actions are known only to God”.

And what about the dragon? That story goes back to the 11th century and was based on a legend which was told in variations even in ancient Greece. But once the dragon-slaying was credited to St George, the saint became even more popular than he had already been.

The tomb of St George in Lod (previously Lydda), Israel. (Photo: Common Licence)

St George, the patron

St George is the patron saint of England, as well as Ethiopia (an image of St George slaying the dragon featured on the standard of Haile Selassie I) and Georgia. Veneration in England goes back to at least the 800s, though St George didn’t become the country’s patron until the 14th century, after the soldier King Edward III put his Order of the Garter under the banner of George. The saint is popular in many countries, almost invariably through his association with the military. In Spain, he is credited with the patronage that helped reconquer the land from the Moors. Many depictions of knights feature the red cross of St George on warriors’ shields.

In Germany, St George was counted as one the Fourteen Holy Helpers, a devotion that had its roots in the bubonic plagues of the 15th century, and lately found renewed popularity during the coronavirus pandemic.

As a Palestinian saint, St George is very popular among the Christians, and many Muslims, in the Holy Land. In times of crisis, many go to the shrine of St George in the village of Beit Jala, near Bethlehem. Every year Palestinians — Christians and Muslims — celebrate the feast of St George, called al-Khader, on May 5, the eve of the Orthodox date of the saint’s feast day.

Many traditionally popular names can be traced back to the Bible or saints. Few saints’ names have been as popular as George — or, as rendered in the original Greek, Georgios, meaning “farmer” — in various local forms, such as Jorge in Spanish and Portuguese, Jürgen in German, Joris in Dutch, Jerzy in Polish, Jørn in Danish, Göran in Swedish, Jordi in Catalan, Jiri in Czech, or Dung in Vietnamese.

Did St George Really Slay a Dragon?

A fresco of St Theodore and St George slaying the dragon. Fresco from c. 10-11th century in the “Snake church” in Göreme, Turkey.

Did St George really slay a dragon? That story goes back to the 11th century and Eastern Europe, and from there to the West. It was an ancient story even then, having been told in variations in pagan Greece. And before it was attributed to St George, its protagonists were other saints, including St Theodore of Tiro.

A fresco of St Theodore and St George slaying the dragon. Fresco from c. 10-11th century in the “Snake church” in Göreme, Turkey

The legend goes that St George found himself in Silene, in modern-day Libya, where a vicious dragon was terrorising the people. At first the people tried to assuage the beast by sacrificing sheep to him. But when they ran out of sheep, the city’s people decided to make human sacrifices. Time came when the king’s daughter was drawn by lot to be sacrificed. Gallantly, George was having none of that, and in short order killed the troublesome dragon with his lance. The people of Silene, all 15000 of them, converted to Christianity. The grateful king sought to shower George with riches, but our hero gave all he received to the poor.

The story of St George and the dragon was obviously a myth, and we’d be arrogant to think that the people of the day were all so foolish as to take it literally. But as an allegory, the story is powerful, and it spoke profoundly to Christian sentiment. Thus the legend grew. It became hugely popular in medieval Europe when it appeared in The Golden Legend, a collection of hagiographies by Jacobus de Varagine.

Even before The Golden Legend, it was popular with Crusaders, who had no problem associating the dragon with the Saracens. In two battles, at Antioch and Jerusalem, the Crusaders reported having been aided by apparitions of St George (and other saints, including St Theodore of Tiro). Thus the lance with which St George killed the dragon became known as Ascalon, after the city of Ashkelon, today in Israel.

And St George, a soldier in real life and a dragon-slayer in myth, has been credited with protection in many battles.

This article was published in the April 2021 issue of the Southern Cross magazine

- The Catholic Ethos - March 3, 2026

- Book Review: That They May Have Life edited by Fr Larry Kaufmann CSsR - February 24, 2026

- Caring for Our Mental Health as Church - February 18, 2026