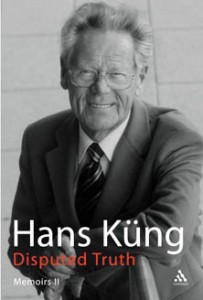

K�ng remembers

DISPUTED TRUTH: Memoirs II, by Hans K�ng (translated by John Bowden). Continuum, London. 576pp.

Reviewed by Paddy Kearney

Disputed Truth is the second volume of Fr Hans K�ng�s memoirs covering the period from the end of Vatican II to 1980. He plans a third volume which will cover the rest of his life.

Disputed Truth is the second volume of Fr Hans K�ng�s memoirs covering the period from the end of Vatican II to 1980. He plans a third volume which will cover the rest of his life.

What is most interesting about this second volume are the insights into that other famous German-speaking Catholic theologian of this era, his contemporary and friend, Joseph Ratzinger � now Pope Benedict XVI. Their lives have �for around four decades�largely run in parallel, then make very close contact, but once again diverge, only to keep crossing time and again�, K�ng writes.

When they first met in 1957 they �immediately got on well together�. At the Council where both were periti, or experts, K�ng discovered that they were �on the same wavelength�, which is certainly not how he would describe their relationship now.

Both came from conservative Catholic backgrounds and both love mountains and lakes. But their upbringing was strikingly different, summed up by K�ng. Ratzinger was �the son of a policeman who grows up in a police station�after his father�s retirement lives in a modest cottage and attends a clerical boys� seminary from the age of 12�.

The policeman�s son grows up differently from K�ng, �a merchant�s son in a hospitable middle-class home in the town square, the focal point for all members of the extended family. This atmosphere is not a well guarded one dominated by police or clergy, but is lively and open to the world�.

Many years later, K�ng concluded that he and Ratzinger represent two very different �modes, forms, styles, indeed ways of being a Christian�. After Vatican II, Ratzinger�s way of being a Christian seemed increasingly to conform with the conservative curial viewpoint which Paul VI bent over backwards to accommodate even as early as the third session of the Council.

Unlike theologians such as Charles Davis, there has never been any chance that K�ng would leave the Church over his disappointment that the curia seemed to block implementation of Vatican II. But he insisted on protesting about celibacy being ruled off-limits during the Council and in subsequent sessions of the Synod of Bishops.

He also persisted in calling for a proper legal process for examining whether a theologian had strayed from Church teaching. The procedure used by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) he finds woefully lacking and has refused ever to submit to their demands: �I will never allow myself to be lured into the Palazzo of the Holy Office and the traps of the proceedings there.�

Following the publication of Humanae vitae, Paul VI�s 1968 encyclical banning artificial birth control, K�ng said that Catholics would be entitled to make their own decision in conscience about contraception. It was not long before he was summoned by the Vatican to a colloquium for which he was given only four days� notice. He complained about this and many aspects of the proposed procedure in a reply sent 30 days� later. Most important was his demand that he be given access to his file, that written questions be made available to him ahead of time as well as the name of the person he would be meeting. Rome did not yet know what a tough character they had taken on in trying to discipline and control Kung: �My whole Swiss character instinctively rebels against being intimidated, humiliated or pressurised.�

A� second major difference of approach between K�ng and Ratzinger emerged in that same year, 1968, during the student unrest at the University of T�bingen in southern Germany, where both were lecturing. Ratzinger�s lectures were on a number of occasions disrupted by whistling, which led to his abhorrence for the whole student movement. This seemed to be a major turning point in his life, causing him to become resistant to all efforts to democratise the Church. He feared being engulfed by chaos. In 1969 he decided to leave T�bingen and take up a post in the much safer environment of Regensburg in his native Bavaria. K�ng, while critical of many aspects of the student movement, chose to stay at T�bingen and to continue engaging with the students.

As a result of the huge public debate stirred up by Humanae vitae, K�ng wrote Infallible? An Enquiry, in which he claimed there was no scriptural basis for infallibility. It was not long before proceedings were commenced against him for this book. He was given 30 days to explain how he could reconcile his views with Catholic teaching. However, K�ng was about to set out on a six-month trip to various parts of the world, and so only replied some seven months later, apologising for the delay but fundamentally objecting to the procedure.

His travels during that second half of 1971 he described as �going out into the big wide world, getting to know new ways, people, lands, culture� � having encounters with the great world religions in a variety of settings. Nothing could have been more different to facing the questions of the CDF.

Despite all the hot water he was already in, K�ng pressed ahead with his theological research and writing, though trying to explain more fully the origin of his ideas. His next major theological work was On Being a Christian, which aims to tell the story of Jesus from the beginning and to reflect on it for our time. This work included renewed demands for a much closer working together of Christian churches, including common celebrations of the Eucharist, the election of bishops, voluntary celibacy for priests, and lifting the ban on birth control.

For all the problems K�ng had experienced during Pope Paul VI�s pontificate, he nevertheless appreciated the protection he had experienced from the pope which had saved him from much harsher action. This of course is what would follow under John Paul II. K�ng did not help the situation when he wrote a scathing assessment of John Paul�s first year in office for the New York Times, an article which the pope saw as a personal attack.

Ratzinger, by this time a cardinal, emerged for the first time as a public critic of K�ng, describing him as �quite simply no longer [representing] the faith of the Catholic Church � and so [he] cannot speak in its name�. K�ng decried this personal attack in a letter to his old friend, saying that it was certainly �not good for our Church�. The good of the Church was something that he himself seems not to have considered in relation to his own negative assessment of the pope in the New York Times.

Ratzinger replied in a pleasant, friendly way, giving no hint of the action which K�ng feels sure had already been secretly launched against him by the Vatican in concert with the German bishops� conference. This was to strip him of the title of �Catholic theologian�, an action which would prevent his continuing to lecture in the Catholic faculty of theology at T�bingen. K�ng was deeply resentful.

�I am ashamed of my Church that secret Inquisition proceedings are still being carried out in the 20th century,� said K�ng, and declared that he would fight to have the decision overturned. There was a flood of protests sympathetic to him, the most poignant of them from Yves Congar OP who, though under no illusions about the problems faced by the Vatican in dealing with K�ng, wrote in Le Monde: �Church of God, my mother, what are you doing with this difficult child, my brother?�

Deeply affected both physically and psychologically for some months about losing his status as �Catholic theologian�, K�ng eventually regained his strength and confidence through reading the messages of support he had received, including 10000 letters of which only 10% were critical. He decided to resign from the Catholic faculty of theology at T�bingen and accept a compromise worked out with the university authorities: he would keep his chair and head a new independent Institute for Ecumenical Research.

As time passed, he began to see that had he not been given this new opportunity, he would not have been able to work with scholars of literature or religion, physicists, psychologists, political theorists and economists. Nor would he have been able to dialogue with various religions and cultures. Most important, he would not have discovered an elementary global ethic.

When next he met Ratzinger, in 1983, the CDF prefect�s first words to K�ng were: �You�re doing well, Herr K�ng?� K�ng replied: �Yes, I�m doing well, Herr Ratzinger, but that�s not what the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith intended.�

The most recent meeting of these two remarkable men, whose life journeys brought them together over 50 years ago and repeatedly since, but whose views are now poles apart, took place 22 years later at Castel Gandolfo, by which time Ratzinger was Pope Benedict XVI. What we know about their four-hour meeting is that by mutual agreement the agenda carefully avoided K�ng�s continuing concerns and questions. A cartoon on the cover of The Tablet portrayed the pope playing the piano (Mozart, no doubt, his favourite composer) and K�ng standing next to the piano singing an aria (not one of his known accomplishments) � all harmony and light. But no further developments flowed from this apparently cordial meeting: contrary to some expectations, the pope has not restored the title of �Catholic theologian� to his old friend.

Despite fascinating insights into the K�ng-Ratzinger friendship, Disputed Truth is not an easy book to read. The reader has to put up with much self-promotion by K�ng and endless minutiae of the conflict with the Vatican, as well as descriptions of tireless research, writing and public speaking to vast and always appreciative audiences in far-flung capitals.

Nevertheless it is essential reading for those with a serious interest in the future of the Catholic Church, Christian belief and the great world religions.

- When was Jesus born? An investigation - December 13, 2022

- Bishop: Nigeria worse off now - June 22, 2022

- St Mary of the Angels Parish puts Laudato Si’ into Action - June 17, 2022