How Abortion Became Legal in SA

Twenty years ago this week, parliament voted to legalise abortion. MANDLA ZIBI looks back on the events leading to that vote, and the consequences of it today.

A few weeks before the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 92 of 1996 (TOP), which allowed abortion on demand for the first time in South Africa, was passed 20 years ago this month, Archbishop Denis Hurley sounded a warning in a speech published in The Southern Cross.

“The great regret we must entertain is that we did not act in time to marshal the support of the so-called silent majority against the pro-abortionist trend.”

However, he added, “we still have the time to proclaim and publicise the traditional Judeo-Christian view, to witness to our faith and to support that witness with fervent and prolonged prayer.”

The Church, together with allied Catholic organisations, did make its voice loudly heard against the ANC government’s intentions to make abortion widely available to South African women.

“The Church made a formal submission to parliament during the public hearings on the law [in October 1996]. Archbishop Lawrence Henry of Cape Town, and a Catholic advocate from Durban, Noel Pistorius, delivered the submission. Fr Peter-John Pearson and I were also present,” said Mike Pothier of the Catholic Parliamentary Liaison Office (CPLO) as he reminisced last week about events 20 years ago.

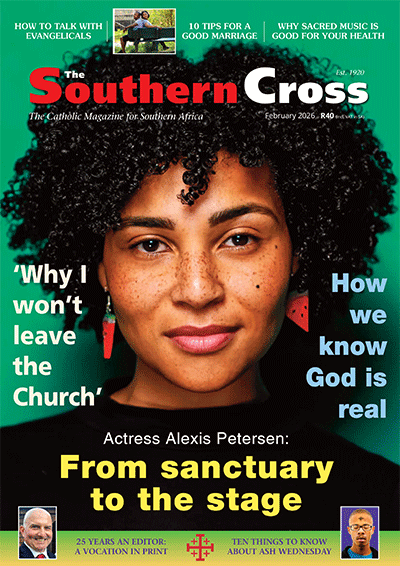

After the meeting, Adelaide Tambo, an MP and widow of former ANC president Oliver Tambo, approached the Catholic delegation to offer dialogue on what could be done about the Bill, which she herself found problematic, recalled Günther Simmermacher, now editor of The Southern Cross, who covered the story for the newspaper.

Catholic engagement with the ANC preceded the submission to Parliament.

“A month or two before the public hearings, a delegation from the Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference (SACBC) visited the ANC head office in order to argue that the party should allow its MPs a free vote on the issue. The ANC delegation was led by Thabo Mbeki and Cheryl Carolus, the party’s deputy president and deputy secretary-general respectively,” Mr Pothier remembered.

“They held to the view that abortion on demand was ANC policy, and that its MPs would be bound to vote in accordance with that policy. So, I am not sure what else the Church could have done. As mentioned, abortion was part of ANC policy, and was also supported by some of the other parties, so there was never any doubt that the law would be passed,” he said.

He added: “It must also be remembered that…there was already a law from the 1970s that allowed abortion under limited circumstances, and it was relatively easy for people to get an abortion if they could persuade a doctor that there was some serious reason for it.”

Archbishop Hurley himself also felt that an appeal to the Constitutional Court against the law would fail, citing a legal tradition which regarded the unborn as not legal persons and therefore having no rights except in some matters of succession to property.

The Christian Lawyers Association mounted a legal challenge to the TOP. In 1998 the Transvaal provincial division of the High Court dismissed it, on the very grounds anticipated by Archbishop Hurley, a case questioning the constitutionality of the act.

Mr Pothier said he had no doubt that many ANC members and MPs were against the idea of abortion on demand, but they were not prepared to make it “an issue of resignation”. To test this idea the SACBC, together with organisations like the Southern African Council of Priests SACOP had appealed to all parties, especially those in favour of the Bill, to allow a free vote.

The ANC had initially made vague assurances towards this. President Nelson Mandela said although the abortion Bill had the full support of the ANC caucus, MPs who had conscientious objections to it might abstain from voting. However, when it came to the crunch, the NEC maintained that no free vote of conscience would be allowed, as abortion on demand was official party policy.

The free vote dilemma

According to a Southern Cross report, a “source” within parliament had declared that if Catholic and Muslim ANC MP alone had been allowed to vote according to their consciences, “the proposed Bill would probably fail, indicating widespread dissatisfaction with the Bill among backbenchers”.

Mr Simmermacher recalled that in an interview in The Southern Cross in June that year, Fr Smangaliso Mkhatshwa — probably the most prominent Catholic figure in the ANC and deputy minister of Education at the time — had made clear his opposition to the proposed legalisation.

If Catholic and Muslim MPs had been allowed to vote freely, the Bill might have failed“When it would come up for a vote, he would be ‘guided by the teachings of the Church’. When it came to the vote, he absented himself from parliament,” Mr Simmermacher said, adding: “I can’t hold that decision against him.”

The late Sr Bernard Ncube, then still a Catholic nun, was a prominent ANC parliamentarian who openly voted for the Bill.

“There were quite a few MPs who privately opposed the Bill,” said Mr Simmermacher, who spoke to several of them. “All of them had to make a very tough choice: to defy their conscience or defy their party. I suppose, your conscience won’t ruin your political career.”

Archbishop (later Cardinal) Wilfrid Napier of Durban, who had been part of a delegation which met deputy president Thabo Mbeki and health minister Dr Nkosazana Zuma in Cape Town in Sept 1996, was also among the most vociferous voices against the Bill.

“My real problem is that the struggle against apartheid was one for the human right to life, but this Bill attacks life,” he said. “We say it would be cowardly for a Catholic MP not to vote [on the issue]. They have to uphold Catholic teaching in public.”

One interesting legal manoeuvre in the battle at the time was proposed by Dr Claude Newbury, the president of Pro Life, who said that for Catholics the “courageous” thing to do was to refuse to certify the entire draft constitution of South Africa until the abortion issue was re-opened. This was after the draft document had been sent back to parliament for amendments that however were unrelated to abortion.

“Courageous action of this nature is essential and urgent if the [campaign] of the Catholic bishops is to succeed,” said Dr Newbury in a letter to The Southern Cross.

Mother Teresa weighed in

The Catholic community in South Africa could not have had a more powerful advocate in the world — bar the pope himself — when Mother Teresa lent her voice to the cause.

In a letter sent to President Mandela, and published in The Southern Cross, St Teresa of Kolkata declared that “the greatest destroyer of world peace today is abortion”.

“If a mother can kill her own child, what is there to stop you or me from killing each other? My dear brothers and sisters in South Africa, your country has set such a beautiful example to the world — that persons of whatever colour, religion or creed can live in peace and unity as brothers sisters. Let us not forget that the little unborn child in the mother’s womb is also my brother, my sister,” she implored.

“What is there, that we must be afraid of the little child, that we must deny him life? Is it because we want an easier life? More comfort? More convenience? More ‘freedom’? God has called us to love. And love, to be true, must hurt. It must cost us something…I am offering my prayers for your country.”

Realising that the inevitable would come to pass, the National Right to Live Campaign called for mass action to protest the Bill. A plan for a National Prayer Rally on November 2 — significantly on All Souls Day, when Catholics remember their dead — was unveiled. This included the handing in at noon of petitions to government institutions by Catholic-organised gatherings across South Africa. At best, isolated groups of Catholics came out in public protest.

And so in November 1996 — parliament passed the Act by 209 votes to 87 (5 abstained, 99 were absent). It came into force on 1 February 1997.

Twenty years later

Twenty years on, Mr Pothier does not believe the political fall-out of the TOP was significant. “I don’t think there have been any noticeable political consequences. Abortion is not a hot-button issue in this country as it is, for example, in the United States,” he noted.

“However, socially, it could be argued that the availability of abortion on demand has further eroded our respect for life,” he suggested.

He explained: “To some extent it promotes a ‘throwaway’ culture that allows people to avoid responsibility for their actions. In this respect I am thinking more of the men who impregnate women, especially young women, and then walk away; they do not have to face the consequences of their fun, whereas the woman has either to bring the child to term and then care for it as a single mother, or deal with the trauma of having an abortion.”

For Colette Thomas, national director of Human Life International in South Africa, aside from the horrendous fact of a million and more abortions since TOP, the spiritual and psychological damage of the Act for women who have aborted, still remains dire.

“When the law was passed, it was said this will bring down the number of backstreet abortions and there would be more control. But we still find more illegal posters up for abortion. There is no monitoring of the counselling given to women before and after abortion,” she said.

“If they say this is a human rights issue, does our country look after the women when they have emotional scarring because of their abortion, when they go through depression or suffer from anxiety? These are just some of the psychological consequences,” she said.

She warned of health hazards linked to abortion such as damage to the womb, the fallopian tubes, possible death from haemorrhaging and future infertility.

Ms Thomas said one of the main instruments in their fight against abortions is prayer, especially in front of abortion centres.

“One of our campaigns in Cape Town since 2012 is 40 Days for Life, a spiritual battle conducted in peace, fasting and prayer to save the life of unborn children by God’s power,” she said.

“The mission is to bring together the body of Christ in a spirit of unity with the purpose of repentance and seeking God’s favour to turn hearts and minds from a culture of death to a culture of life, thus bringing an end to abortion.”

Next week: A Catholic response to abortion today.

- When the ‘Holy Bird’ came at Pentecost - June 1, 2022

- Marist Brothers Celebrate their Name! - September 10, 2021

- Mary Magdalene – From 7 Demons to Disciple - July 22, 2021