Compassion and Consolation

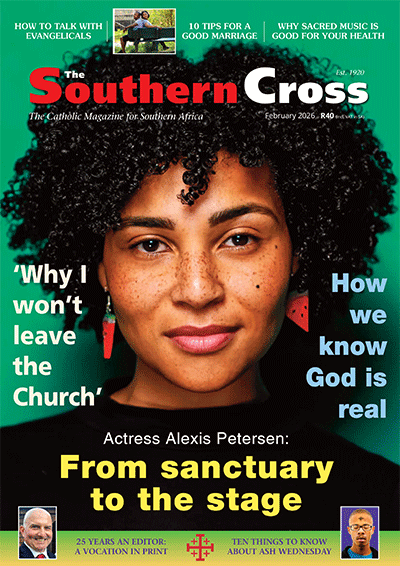

Paddy Kearney (right) with Archbishop Denis Hurley on September 11, 1985, the day of Paddy’s release from political detention as a result of a Supreme Court ruling.

By Dr Raymond Perrier – Compassion is one of those words that is used far too lightly and we risk losing sight of its true meaning. The origin of the word spells this out: it means “to suffer with”, so much more than just feeling sympathy for someone.

This month’s Jubilee of Consolation falls on the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross. We have a further opportunity to reflect on the themes of consolation and compassion with the feast of Our Lady of Sorrows (Mater Dolorosa) the day after.

The prayers, psalms and readings of those feasts are a reminder to us of the suffering of Jesus, and the sorrow felt by his mother as she witnessed his suffering. But we are called in these feasts not just to observe or even to commemorate but to feel compassion, to suffer with those who are suffering. And we are reminded that Jesus chose to suffer to show his own solidarity with those who are suffering.

Forty years ago this month, Paddy Kearney, the founder of the Denis Hurley Centre, had his own experience of suffering. Police marched into his office and took him away for indefinite detention without trial. Their hope was that, like so many other prisoners of the apartheid regime, he would be forgotten and left to languish in a cell. Perhaps their real hope was that, like some, he would be driven to the despair of suicide, or might “accidentally” fall to his death.

But the forces of darkness did not count on the power of Christian faith. Paddy had no choice but to go quietly into solitary confinement. But while there, he found sustenance in the Scriptures. He later related:

“In this very trying situation, I read the Bible as I had never read it before. I took the time to stop and reflect and pray, and found the Psalms especially comforting. Also, I remembered words of hymns: ‘Be not afraid, I go before you always, come follow me and I will give you rest.’ This made me aware that God was going before me even in this painful experience.”

The hymn he mentions is one that many readers will know. The psalms are of course a part of every Mass we attend. But how much do we notice what these words are saying? I am struck by Paddy’s phrase: “I read the Bible as I had never read it before.”

During the ten years he had spent as a Marist Brother, Paddy would have recited the psalms regularly as part of the Liturgy of the Hours. This is the monastic practice of interrupting the day with prayer at key moments. A fellow novice of Paddy shared a memory of what that practice was like for them:

“As religious Brothers we went to say prayers — but not to pray. We knew the psalms off by heart, but did we pray them? We were concentrating more on performance and not actually meditating on the words.”

Psalms of comfort

As Paddy actually read the words — and in gaol he had the time to do so — he noticed how many of the psalms were written to give comfort to people when they were suffering. Sometimes, as in Psalm 18, the Lord promises to rescue those who suffer; at other times such as Psalm 145, there is comfort in knowing that the Lord is suffering alongside us.

It is telling that Paddy later insisted that at every ecumenical Good Friday Service in Durban, the hymn “Were you there when they crucified my Lord?” would be sung. With these words, we are being challenged to answer whether we stood by Jesus as he was being crucified. But the true impact of the song becomes clear when we remember it was written by enslaved African-Americans. The song asks us if we stood by the suffering Christ, but also reminds us that the suffering Christ stood by those slaves in the cotton fields.

These songs and psalms will be used this month in a service to mark the 40th anniversary of Paddy’s detention, to be held at St James Anglican church in Durban. Modelled on the service of Evensong, we will reflect on the ways in which the psalms can help us in times of suffering. Included in the service will be new work by award-winning Durban poets who express in their own ‘psalms’, in English and Zulu, the feelings of despair and hope of traditional Scripture.

Paddy would often quote from the Jewish writer Elie Wiesel’s memoirs, Night. Wiesel was traumatised when, as a warning to others in the concentration camp, a young man who had tried to escape was left hanging from a tree. Wiesel asks himself where was God in this story and he answers, pointing at the limp body on the cross: “There, there is God!”

A similar image appears in the famous 1954 Hollywood film On The Waterfront. A priest (played by Karl Malden and based on the real-life Jesuit Father John Corridan) is trying to give hope to the striking dockworkers in New York and they ask him where Jesus is. And the answer they receive is that Jesus is there with them: “Christ is in the shape-up. He’s in the hatch. He’s in the union.”

It is good that we can give comfort to people in their suffering by telling them that Christ is with them. But these are cheap words if we do not follow them up with action. When the psalms talk of a God of compassion, it is a God who rises up and fights for us.

A legal precedent

While Paddy was drawing comfort from reading the psalms, Archbishop Denis Hurley was fighting a bitter court battle which succeeded not only in releasing Paddy after 17 days of detention but also protecting future activists from detention without trial, at least until the declaration of successive states of emergency.

This legal precedent is still taught in law schools; the UKZN 2025 Moot competition will in fact take this as its theme.

I do not know whether law students read psalms, but they are definitely being urged on by the actions of a fearless psalm-inspired archbishop who 40 years ago used his power as a religious leader to help set an important legal precedent.

The great South African theologian Fr Albert Nolan OP reminds us that compassion requires us to show solidarity with real people in the reality of their suffering:

“Where is God in South Africa today? God can be heard in the crying of children. It is not their innocence, their holiness, their virtue, their religious perfection that make them look like God. It is their suffering, their oppression, the fact that they have been sinned against. Suffering makes God visible as the one who is sinned against. The suffering of the people of South Africa is one of the great signs of our times. It is the sign of God’s presence as the crucified Christ. It is the sign of the cross.”

These words are as true today as when they were written in 1988. Apartheid may have ended, but suffering has not. We know where Jesus is in that picture of a suffering South Africa. But where is the Church? Where are our leaders? Where am I as someone who claims to be a Christian? How do I truly show that I am willing to suffer with those in need?

- Ring the Bells for the New Year - January 5, 2026

- Pope Leo’s First Teaching - December 8, 2025

- Are We the Church of the Poor? - November 15, 2025